Celebrities are a good way to consider the differences between being young and old and also considering the significance of being old.

It is not true that “The medium is the message”, a remark and approach to modern media stated by Marshall McLuhan, and widely circulated in the Sixties. But the medium can make it easier to develop or appreciate a message if you use a new medium, as happens when an x-ray, which is the medium, can reveal the message of an abnormality. Such is the case with old age as that is revealed by the comparison photographs provided in YouTube shorts that juxtapose young celebrities, both male and female, when they are young actors and actresses juxtaposed to photographs of them just before they died. What is the same and different between these juxtaposed positions? The shift in the cultural interest in aging is itself worth noticing. Dante placed the various people in Hell and Purgatory at the prime of their lives perhaps to make these villains heroic rather than villainous or victimized given the pains they endure forever or just millennia. But in our times we look at the contrasts, the before and after being the long arcs from youthfulness to being all but dead, ravaged by age and infirmity. Look at these people in these photographs closely.

Audrey Hepburn (candids)

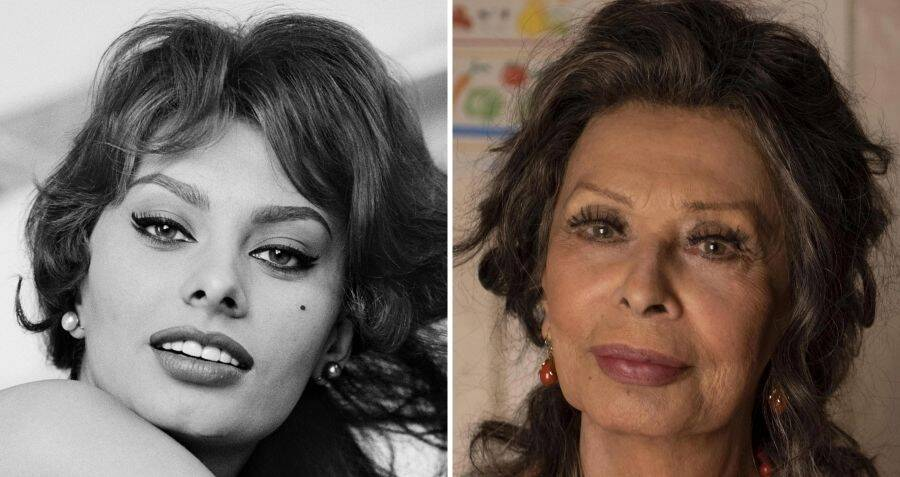

Here are some obvious but significant aspects of aging. People age to different degrees. Elderly women get lined and puffy, but Audrey Hepburn retained her pixie-like and endearing face for her entire lifetime. Gina Lollobrigida and Sophia Loren became crones but it wasn’t just because they had always been pulchritudinous. Jane Seymour, Shirley Jones and Julie Andrews added a bit of weight but kept their shape and faces till they died. We never got to see if Marilyn Monroe would age gracefully but we know that until her very late years Elizabeth Taylor remained well crafted, as did her bete noire Debbie Reynolds. Men, as is often observed, age better than women. They become more lined and craggy as they age but retain their shapes though sometimes, like Martin Landau, adding a beard to make them full faced. (Remember that sometimes, as in tbhe differential aging of the sexes, biology may be more imprtant than culture or circumstances.)

Sophia Loren (studio, candid)

What remains of the older movie stars has their penetrating eyes, their pleasing and enigmatic smiles, their posture and poses that show that however much their bodies deteriorate, their selves remain: they are alert and observant, looking out at the world with the sadness or bemusement they probably retained through most of their lives, how it was that they engaged life. Each person has his or her particular presence despite the fact that old people look like one another. That means that the self usually outlasts the body unless dementia takes its toll. We are alive inside while the body fails us which is a blessing in that people are alive inside their decaying surroundings even if sometimes as in ALS, the body becomes a coffin. That was very different from the way William Hazlitt, writing in the early nineteenth century, thought about the old, which was that they were ready to die when they died because they had by that time deteriorated in spirit as well as body, perhaps because the various infirmities had diminished mental capacity because of pain and general condition and so the actual death coincided with the spiritual death and so seemed fitting or just while in the present day death seems unjust because it is wrenched by one or another failing organ or particular disease while the mind was still lively.

How do we assess beautiful people? Sometimes, as in a Thirties Busby Berkeley musical, a bevy of beauties flash through the screen, each face for only a few seconds, and all you, the viewer, can do is just feel the aesthetic of the objects being beautiful, each in their own way. It is the experience of abundance and awesomeness. Sometimes, in the Belle Epoch, and at other times, you can linger with a particular portrait and study the woman’s mystery and try to figure out why she is attractive. The pert nose? The tilt of her head? The prominence of her cheekbones? The point is that there is a mystery to be solved as if there were a way to show appearances to be tied to an inner reality. The beautiful know they are burdened with being looked at as if they could be read. But when women age, the question shifts to what it was that made her old, that damaged her beauty. Too puffy? Neck muscles like cords because the neck has lost its fat? And what is now to be retained in the pose and presence of the elderly ex-beauty, some resemblance to the time at her highest beauty? My surmise is that the women who arrive at old age are not ashamed of having deteriorated or are for the most part desperately trying to cover up their deterioration. They are simply trying to look presentable, their self staying within themselves and appearing to be what they always have been. If that is true, then old age is not a stigma as is the case with a deformity but another state of being continuous with prior states and so neither shameful nor admired, just the fact of life. That is very different from what Cicero said about old age which people met with character if they had it rather than reproaches of oneself for being more frail or ugly, a Stoic acceptance of what had to be, but rather a continuation of a life in this sense in disrepair, and therefore also a kind of mystery in that the critic of a portrait of an older beauty also has to also be challenged to think how the appearance is related to the inner self, whether Sigourney Weaver or Tuesday Weld, each preserving a kind of graciousness as well as aware of how much better they looked, not so much, I think, to mourn it, as to keep in cherished memory what they looked like best. So being old is not about death or deterioration but being a stage in yourself aside from the fact that it is the last one, long may it last.

Gary Cooper (studio)

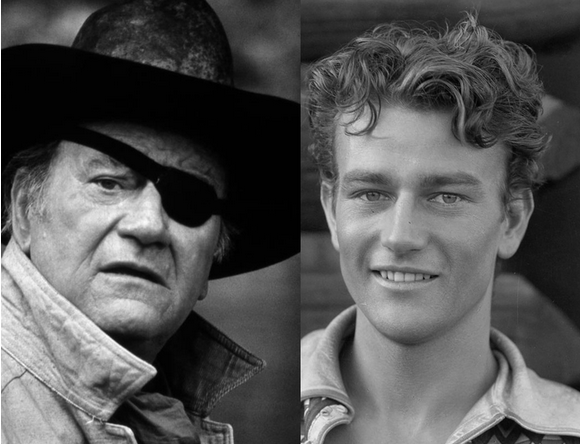

People who age may get significant advancements in their careers in the course of their lives. Junior accountants can become senior accountants or firm managers and interns can become attending doctors, these based on skill and experience, while people may only move up from filling in on an assembly line to shift managers and small entrepreneurs from running a small grocery store to a small supermarket or even a chain of supermarkets. Those are the careers they create in their lifetimes, the pinnacle being the corner office or a paid off mortgage, Celebrity movie stars are more closely tied to aging rather than just the years whereby to work forward, they are tied to their bodies because, as the expression goes, their faces and their posture as well as their voices are their instruments and so it is remarkable to notice how actors can provide long careers, having to change over time to adapt to their aging. Bette Davis was the attractive sultry and lowdown temptress in “Of Human Bondage” in 1934, then the young women and the matrons in the Forties and then an old hag in “What Happened to Baby Jane?” in 1962. Myrna Loy was the femme fatale in “The Black Watch” in 1930 and then the young wife in the Thin Man movies and then the wife with an adult daughter in “The Best Years of Our Lives” in 1946 and the grandmother in the 1950 “Cheaper By the Dozen”. Gary Cooper was the young aviator in silent movie “Wings” in 1927 and ended up as the elderly man who had a fling with a young woman in “Ten North Frederick” in 1958. Some notable stars have brief careers, Grace Kelly decided to give up her film career to marry a prince and Clara Bow was felled by mental illness. So a film career shows aging taking place, its various accommodations and its continuing strands, John Wayne the slender laconic man in 1939’s “Stagecoach” becoming the laconic and corpulent person as Rooster Cogburn in 1975. We measure our own ages by seeing into which celebrity lives our own lives have intruded by watching some party or all of their careers. The young Katherine Hepburn, who I know from early on, was much the same person in her late movies such as “The Lion In Winter” and “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?” before she left my scene.

John Wayne (studio)

Dante is rather harsh in thinking that people could be sent to Hell or Purgatory for some single events of moral failure on the grounds that such events show the persistent flaws of their characters. But he is very much to the point in that a single life is a span to decide what a person is like, for a person to make their mark on life, and so think of life as a career to test the mettle of people. Everybody does that and celebrities visibly show their talents as being attractive and amiable, whether as character actors or major stars or themselves flickering out after a few films. The age and station of the person shows a celebrity career as having a timeclock that can be altered by facelifts and different roles. Andy Devine and Gabby Hayes were always character actors but John Wayne since 1939, was always a star. We watch him be himself and change and that is what all of us do, moving from prodigy to child bride to patron or matron and wise elder, catching up with ourselves, knowing that as soon as you have learned how to be a child you have to learn how to be a teenager, never quite mastering an age before it is past. Reinventing is maddening and celebrity reinventing is a visualization of a truth of human nature in the lives of people who present themselves to the public view. Some movies are profound, and movies as a form of story are also profound because the celebrities, the nature of celebrities, is to see these things happening before our eyes. We see them in youth in their time settings, in the clothes and customs and preoccupations of a time and then can time travel to a nearer time with its own customs, settings and preoccupations and see how they can do there. William Powell could last from “My Man Godfrey” in 1936 on because a manner of sophistication works everywhere but Marlon Brando had to abandon the kitchen drama of Stanley Kowalski, and he did, many times. He was a man in all seasons, while most of us are not, gravitating to a particular time which is our time, the one in which we feel comfortable, often the one from which one’s character is formed.

There is another way to use comparisons between celebrities in their young adulthood and their old age. Because celebrities are revealed in their personal lives as well as their professional ones, their life span across their age shows what people can make of themselves in the one life to which, the photos show, their lives were allotted. Did they flash on the screen early in life and then go dry and spend the rest of their lives with regret or pride at the time before? Shirley Temple was a charming pre-adolescent, became less charming as a teenager, and superfluous as well as doughy as an adult U. S. Representative to the United Nations while Natalie Wood remained charming and attractive until her death in her forties. Rob Reiner changed from becoming a very able actor in “All in the Family” into a very accomplished film director during his adult years.

There are three ways in which people can measure the success in their trajectories. There is the accomplishment of producing a work, such as a poem or painting, what Marx thought transformed labor into work. There is the creation of an activity, such as starting a business or being a good person, which is what religions favor as the best ends of life. There are the creations of memories or records of one’s own life for their own sake, which has recently become popular with selfies for recording having gone to a Starbucks, such events neither artful nor significant. The thing is that celebrities do all three of these things. They have filmographies. They experience being in the limelight. They are photographed for the trivial things they do and remarked on in print for doing casual things to the point that some of them cherish ordinary life, which means being anonymous, as happened when Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward removed themselves to Connecticut, flying to LA only for work.

What is to be made of such trajectories from the point of view of their elderly visages? The sardonic view that the person with the most toys when they die is the one who wins is partly true in that people leave after themselves foundations and art collections and apportion their wealth to their descendants, controlling people after their grave. But dead people do not look at the future that will happen after they die unless they are superstitious, just as they cannot trade in their accumulated good deeds for how things will be treated about you in your afterlife. Dead means all dead. So all you can say is that whoever wins is the person who lives longest while remaining mentally intact and without much discomfort. Maybe that is why the celebrities in old age are smiling.