Two weeks ago, I might have thought I would have to say I was wrong about what I had said two weeks earlier, which is that there was not much difference between the various candidates for the Democratic nomination for President, that they were all New Deal Democrats, and so we would make a choice on the basis of personality, which is a good or a bad thing depending on whether you think that people of real character will shine through, the alternative being that we will chose a charlatan or simply someone who has a tic or an expression that we find charming. What had gone wrong was that so many of the Progressive Democrats seemed committed to outlandish “Socialist” proposals and so there was a real division between the progressives such as Kamala Harris, Bernie Sanders, and Elizabeth Warren, on the one hand, and the mainstream Democrats, such as Amy Klobuchar, Joe Biden and Sherrod Brown, the others not yet having chosen sides. What a difference a few weeks make.

Read MoreThe Structural Underpinnings of Free Speech

Free speech is the experience of knowing that you can say anything you please without fear of governmental or other institutional authorities. You have free speech when you sound off in a high school class about politics because you know that school is a protected space where a variety of opinions are allowed even if some people may disapprove of what you say or even criticize you for those opinions but must, nonetheless and however grudgingly, admit your right to hold them. Free speech does not mean you are free to insult people, because that violates basic rules of courtesy, but it does mean that contrarian opinions or even fresh and unfamiliar points of view get a hearing, the only control being the informal ones that have to do with customs which can be so rigorous, as in a religious community, that saying unholy things can lead to ostracism or perhaps merely severe rebukes, these enough to make such a community not to be one that allows free speech. Free speech, as an experience, then, has about it the sense of liberation, individuality and democracy. Free speech is also a term that refers to the institutions which, like that high school, protect and further the activity of free speech, and this post is concerned with what are those institutions that led to the establishment of free speech as a characteristic feature of democratic regimes.

Read More6/23-Longevity

Let us turn to the other major source of information about primitive times that is found in “Genesis”: the connective tissue of genealogy. There is, first of all, a very brief story associated with the name “Lemach”. The story acts as a commentary on the Cain story, showing that the message of God’s forbearance with the first murderer will be lost on generations of people more intent on revenge than on anything else, and so the Cain story is also a false start, because its message does not become part of human consciousness, only a message within the “consciousness” of “Genesis”, as that can be misread by the countless people who will read “Genesis” and claim to take it seriously.

Read MoreJohnson's Dictionary

The importance of Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary is not that it was one of the first or that he had some piquant definitions but that it took a very different approach to language than is generally taken by philosophers. Samuel Johnson does something very radical in his dictionary. He posits the idea that for any word, whether simple or complex, everyday or esoteric, there is another word or string of words that can be generated in English that is its equivalent in meaning. Johnson provides some forty thousand examples as proof of his proposition. That is a remarkable thing to claim about language. However much it expands, whatever new words are added to its vocabulary, there is some other set of words it can be mapped to. Why this is the case, Johnson does not explain. He was not that kind of thinker. But he was a student of language and so could invent or find, take your pick, these equivalences which made language not a closed system in that words could only refer to other words, but an open system, in that new words could always be meaningful because they could be referred to old words. This is a characteristic of language in general, that it expands in this way, and it is not a characteristic which holds for other systems of thought.

Read MoreThe Moral Lessons of "Now, Voyager"

The poor quality of the movies up for this year’s Academy Award for best motion picture reminds me of the time when movies were indeed better than ever, which was the period of the late Thirties and the early Forties, which produced not only “The Wizard of Oz” and “Stagecoach” (I am still leary of “Gone With the Wind”, another 1939 blockbuster) but also, in the early war years, such movies as “Random Harvest” and “Now, Voyager”, both from 1942, and both heavily melodramatic in that people were given psychological excuses for being out of touch with their own lives and so needed to find ways to integrate themselves back into a social life somewhat abbreviated from a normal life, all the while the characters managing to retain their self respect and not give in to feeling sorry for themselves, which is the constant risk in melodrama. In “Random Harvest” that meant Greer Garson had to settle for a sexless marriage to the man she had known as her husband before he fell into amnesia and in “Now, Voyager” that meant Bette Davis settling for a long term affair with Paul Henreid because circumstances, including themselves, stand in the way of marriage.

Read More5/23- Primitive Times

In “Genesis”, right after the story of the Creation, there is the story of Adam and Eve and their family. It is a story often taken as the archetypal account of the human capacity for disobedience and murder. Then, later on, there is the story of Abraham and his descendants told with such density that it contains as much material as a series of novels. That saga carries a set of families into, among other things, encounters with the world civilization of the Egyptians and thereby sets the scene for the epic of liberation provided in “Exodus”. The redactors of “Genesis” fill the time between the richly detailed close ups of Adam and Eve and their family and of Abraham and his family with the more fanciful stories of the Flood and the Tower of Babel, those set amidst genealogies that, like movie fadeouts, show the passage of time.

Read MoreWhat's Wrong With Slavoj Zizek

Slavoj Zizek is a contemporary Slovenian social thinker who is well versed in Hegelian Idealism, Marxism, Lacanian psychoanalysis and film theory and, I am told, is very well thought of among young people. It is easy enough to see why he is appealing: his broad range of references, his graceful writing style, his willingness to bring in what would not seem apposite subject matters, but even there you have the beginning of a sense of why he is unreliable. He mentions “Gangnam style” which was a South Korean video and dance that made it into popular culture for a little while, but doesn’t have enough weight, less important than hoola hoops, for saying something about society. He reflects on the relation of North to South Korea, possibly because he had lectured in Seoul, when it would be more important to evaluate the meaning of capitalism in the United States, still its center, and so I am pressed to ask this question of his “Trouble in Paradise”, the title itself a reference to an Ernst Lubitsch film: what does he mean, really, by capitalism, other than it is the opposite of what is not yet, which is true socialism? That Hegelian opposition will not do, and so let us tease out his definition by bypassing his fascination with the Hegelian trick of turning everything into a negation or a negation of a negation, which is a philosophical parlor trick that doesn’t mean anything at all. Zizek says, with glee, that capitalism is a system which has two negatives: those in the surplus labor pool, who can’t get jobs, and those in the pool of educated persons who do not think they need jobs, and so capitalism includes both those it needs to keep the price of labor down, and those who it creates who seem surplus to the economy as a whole. All Zizek is saying in this formulation is that everything that happens in capitalism is a product of capitalism and so part of what is a combined mind set and social structure which does not have mechanisms which are either more or less essential. That holistic approach does not do justice to the complexity of what we know to be capitalism, where levels of taxation and central planning differ in, let us say, the United States and Sweden.

Read MoreSargent's Story Pictures

John Singer Sargent is best known, of course, for his portraits of pretty society women in fancy gowns. Sargent does not use any symbolism in his painting. That would mean one image stands in place of another image or idea as when a dove represents The Holy Ghost. But, for Sargent, an orange sash is only an orange sash. So how does Sargent catch the intellectual interest of his audience without symbols? He does so by turning these hired portraits into story paintings, which means that his audience is invited to tell stories about them, a story being a narrative that gets from one place to another and has some suspense about what will come next. These stories are there in the pictures but waiting to be found, the viewer the one that has to conjure them up, though the clues for doing so have been supplied by the artist in the way he poses or dresses his subjects.

Read More4/23- Noah the Technologist

Noah was a good enough engineer, whether he got the plans from God or dreamed them up himself under the inspiration of God, to correctly execute these very ambitious plans. The plans are spelled out in detail. The ark is to have three levels. It is to be caulked both inside and outside. It is to be three hundred cubits long, fifty cubits wide and thirty cubits high. The dimensions of the ark are given so distinctly that they serve the literary purpose, of course, of concretizing the description and so make it as if it happened. But this is an interesting set of descriptors. “Genesis” could have said large or very large or as tall as a cedar of Lebanon or some other metaphor for size. “Genesis” does tend to exaggerate when it gives particular numbers, as when it gives the ages of the generations between Adam and Noah. That makes the story legendary: an exaggeration of what might have happened in the past rather than treating the past as having a very different set of processes than does the present, which is what happens when a mythology is created. There seems to be a different reason for concretizing here in the Noah story.

Read MoreDemocracy and Genre Painting

Genre painting is the name given to a genre of painting that flourished, among other places and other times, in Mid-Nineteenth Century America. Genre painting in America portrayed the informal social life of a supposedly still unsophisticated and largely rural America, this movement ending entirely with Winslow Homer’s “Snapping the Whip” (1872), that painting of boys at school recess that is perhaps better known today for its 3D effect of having its participants look as if they are on the verge of breaking out of the frame. These American genre paintings portray people grooming and selling horses, dancing, white people mixing with African Americans, and much else that could be considered informative about what life was like back then if one could trust inferences that are made from an art form, whether that is literature or painting, about what is really going on in the social life of the times. The art historian Elizabeth Johns makes such an attempt with regard to American genre painting and concludes that the paintings present a number of types so as to take a condescending and humorous view of their subject matter and are therefore not to be trusted as a serious set of pictures about the way things were because the pictures are designed to please the city swells who commissioned them. I disagree. I think it is possible, if one is careful, to draw inferences about reality from what might indeed have been painted as fanciful or stylized presentations of the life of the times. More particularly, the pictures, or at least some of them, tell the story of the emergence of democracy in the United States, a subject that historians of the time find crucial but where there is not enough of a documentary trail to explain how that remarkable event took place, something that did not arrive in Great Britain until the Reform Bill of 1886, some fifty year later.

Read MoreCultural Mutation

Cultural mutation is a way to understand what is happening in a number of politically charged issues from race relations to foreign policy even though social scientists do not usually treat culture as something subject to spontaneous or creative change. Culture is usually regarded by anthropologists as the continuing way of life of a people, embracing customs, laws and beliefs, and so very stable and self-perpetuating and arising for unknown reasons, while sociologists emphasize the way culture reinforces the social structure that exists because it is transmitted by institutions that are answerable to the structure, as when television transmits what its advertisers will approve of, social media a maverick in that there opinions percolate up from the people, and there is an understandable reaction by which government and other institutions of culture, such as the press, want to see the social media controlled so that they do not promulgate unpopular opinions. Culture is also taken to be a bridge or the medium through which change takes place in that culture diffuses innovations across a population, as when it spreads knowledge of vaccination, even though it is not responsible for original ideas. These theories are contrary to the perspective of humanists, which sees culture as the source of new ideas, whether in science, as when Darwin and Newton invent new perspectives because of their own ruminations while building on precedent thinkers, Darwin a mutation on Malthus and Lyell, while Newton was contemplating Copernicus and Galileo-- and vaccination was, after all, invented by a particular doctor in England on the basis of his observation of cows and the lack of smallpox among cow maids. Ingenuity and insight count. The humanist perspective can be applied to current events.

Read More3/23- Noah and God

The redactors of “Genesis” were concerned with the development of technology, something that is immediately experienced, pervasive, and stands out from the natural world as a human artifact that confounds otherwise ordinary senses of scale and distance. That is true of even the creation fable that leads off “Genesis”. The creation fable does not offer creation done instantly by a powerful god nor does it relate a story of conflicts between gods that would motivate a god to create the world. Rather, as was suggested previously, it offers the set of processes that have to be performed in a particular sequence whereby the natural world, as humankind would know it, might become established. What is more fundamental comes earlier in the sequence. The separation between night and day had to proceed the separation of the water from the land and that had to proceed before the animals could be created. God stepped back after each day’s labor to note his accomplishment. So He made the heavens and the earth rather than simply called them into being. Joseph, at the other end of “Genesis”, offers the social technology whereby the results of a famine can be avoided. That, on a more mundane level, is also a story of how to get from here to there, the creation of an agricultural surplus a process and not simply an intrusion.

Read MoreCampaign Rhetoric

The conventional wisdom is that political parties try to correct the mistakes they have made the last time or two around. So the Democrats didn’t want to nominate another clearly Liberal and Northern candidate after Mondale and Dukakis were defeated and so turned to Bill Clinton, a Southern Centrist who might pick up some of the states that had gone to Jimmy Carter, who was from Georgia. And so the Republicans, in 2020, will alter their primary structure so as not to let the nomination go to a crazy, by then having been saved by Robert Mueller from having to renominate Trump. Democrats, for their part, are going to look for a candidate with a little more personal oomph than they got from Hillary Clinton, who they blame for having lost the race, though we still do not know whether that was the result of of Comey or Russian interference. Remember that her margin over Trump went up after each of the three presidential debates. Those who tuned in knew who was and who wasn’t Presidential.

Read MoreThe Limitations of Painting

One of the things that made Sargent a great painter was that he appreciated the limitations of painting. At least for two hundred years before he did his work, painting had not carried philosophical messages or meanings encoded in symbols but rather did what it was capable of doing, which is to show what things look like. Sargent has no symbolism, no iconography, only what people, particularly, look like in their faces and in how they dress and in their presentation. What Sargent gets from accepting that limitation is an attention to detail that allows him to pick up the telling detail that gives a picture drama even if not anything that could be called meaning.

Read More2/23- Adam and Eve

The creation of woman should not be seen as an afterthought by a God who had previously provided each of his animals with a mate but overlooked doing it for Adam. God may have thought that Adam was a special enough creation, meant to rule over the rest of it, and so he did not need a mate. But either God changed his mind about that or always knew that he would make a special creation later. Woman was a special creation so as to emphasize that in the actual world the relation between man and woman is not like it is with the pairings of the other animals; some special kind of creation was required. Eve was as close to Adam as his own rib. As a legend might, the story of Eve’s creation suggests that woman has thereafter an ambiguous relation to man: part of him, descended from him, and yet a companion to him, and so clearly something different from what happens with some other created species no matter how much it might occur to a son of Adam or a daughter of Eve that the two sexes had different natures. We can see this more clearly if we consider the type of literary undertaking the story of the Garden of Eden is.

Read More1/23- The Creation Fable

This is the first of a twenty-three part series on the Bible. The general theme is that the Bible is for the most part in the vanguard of those who want to secularize history. That means that the authors of the Old Testament, and even of the New, are interested in dispensing with mythology, reducing the number of supernatural interventions in history, and moving the center of religious concern away from magical moments to moral questions.

The creation story in “Genesis” is a far more modern thing than it is usually credited with being It is a kind of philosophical presentation and so very different from mythology which, as Ovid, that great student of mythology, noted, there are always biological transformations of things even while the gods remain subject to the forces of nature and the raging of human passions. Narcissus becomes his image but only symbolically, and not all narcissists become their images, which is what happens in a fable. The creation story is best explained as a fable, which is a story that explain a set of circumstances that do not seem to be created but which somehow were at a point in time and have become part of nature. Tigers have stripes and the Red Man got baked right, neither too much or too little.. Fables suggest that there is a history for what seems natural, a sometimes serious, sometimes fey attempt to make explicable what seems not to need explanation or else to make explicable something which seems paradoxical: how something could come into existence when it already had to be there.

Read MoreJohn Sloan's Distinctive Cityscape

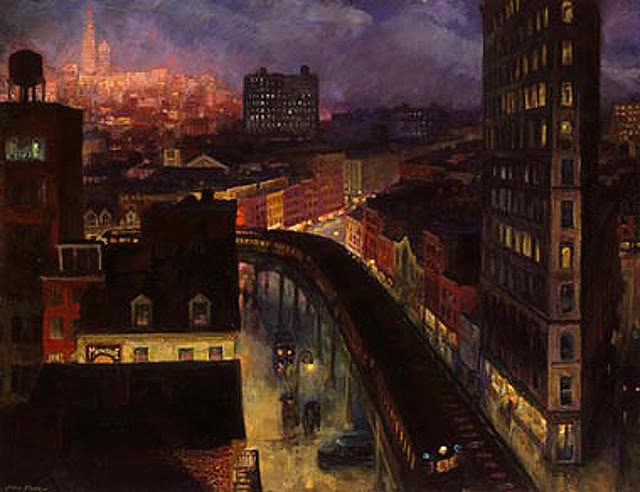

John Sloan’s well known painting “The City From Greenwich Village”, painted in 1922 and now hanging in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D. C., is a prime example of the Ashcan School, called that because it focussed on the grimy realities of city clutter and constant construction and the working class people who lived there. The painting remains striking because it provides a distinctive and very American view on the nature of city life, one quite different from the idea of urban life found in British, French and French presentations of citylife. James Whistler takes London bridges and turns them into swathes of dark color on a dark background to create paintings that are forerunners of Rothko. Cezanne fills the wide boulevards of Paris with crowds of people. Ernst Kirchner and other German Expressionists portray a Berlin crowded with strange looking people enjoying the nightlife. Sloan emphasizes, instead, how important is the physical aspect of cities, both the architectural structures and the architectural infrastructure. Spatial relations are more important than ethnicity or crowd psychology in explaining citylife.

Read MoreThe Upside of the Shutdown

Optimist that I am, let’s look at the upside of the government shutdown. Sure, eight hundred thousand government workers (not all Democrats) are without a paycheck, and there are the additional thousands who are lunch counter operators and dry cleaners who will never be compensated for their lost revenue. But the important point is that the border wall issue is one without content. Republicans fudge the difference between a border wall and border security because only political people think the wall is needed and Trump thinks so only because he became entranced with the term during the campaign. Trump is also the hands down worst deal maker of all time. He could have gotten twenty five billion for his wall last year in exchange for a bill guaranteeing the Dreamers a path to citizenship. He agreed to the deal when it was presented to him by the leading Democrats and Republicans but reneged on it after Stephen Miller got his ear and suggested the deal also include changes in general immigration laws so as to bar what they call chain immigration, which means uniting families, such as, for example, Melania’s family, brought over under those terms to the United States, as well as getting rid of a lottery for some immigrants. Miller also wants to cut the number of legal immigrants allowed into the United States. So we are left with Trump now shutting down the government to get a fraction of what he could have gotten if he had really thought the border wall were a policy issue, which he now claims, rather than a campaign slogan.

Read More9/9: Jane Austen's Critique of Kant

Lest the message of what might have been is lost on the reader of “Mansfield Park”, Jane Austen steps forward as she opens the novel’s last chapter to give in a form even more terse than the rapid fire narrative of the events of the prior few months the denouement of her story. Far from drawing a moral message of how everything is resolved for better or worse, how people pair off as nature intended, with Fanny getting the Edmund she rightfully deserves, she shows that Fanny gets Edmund because that is all that she deserves, in the sense of a person who she is prepared to deal with and who is prepared to deal with her on the terms of the claustrophobic life of Mansfield Park now doubly enclosed by the moral Methodism which Mary quite properly characterizes as Edmund’s. It is not just that both Edmund and Fanny were quite right in thinking that they could not bear the constant sensations of dealing with the candor and overt feeling of their previously intendeds. It is also that they have each been more true, all along, to their own feelings of self respect which they see mirrored in one another than they have in the interests of the family at all.

To the reader’s surprise, there is no recrimination by the family for the role Fanny played, largely through inaction, in bringing about the scandal in the family. To the contrary, she seems all the more indispensable to Mrs. Bertram, and seems to Sir Thomas Bertram to have been morally correct in her reading of Henry, though she has her own silent misgivings about whether or not she would have not eventually accepted him if he had not been so foolish as to fall again, at least temporarily, for his prior love. Mary was quite right in thinking that a little encouragement by Fanny might well have saved him from following his impulses. Moreover, the family, in its morally diminished state, with Maria dishonored and Julia badly married, turns to Fanny as a reminder of what they themselves once were, an icon of country respectability, which she has become more than they ever were. And so her eventual marriage to Edmund, which had been unthinkable because of her rank, and because she was sisterly to him, becomes thinkable as the emphasis is placed on her as a distant relative who has risen in manners well enough to give substance to the feeling that the family is respectable once again, though she brings nothing else to the marriage.

Mrs. Norris, who had always served as the family Cassandra, reminding them at the very beginning that this is the way things might turn out, finds herself the subject of Sir Thomas’s disapproval, perhaps because she is a reminder of the extent to which the little girl who was taken out of charity to serve as a high level companion to his wife, has become the dominant figure in the family, replaced his own daughters in his favor, which seems particularly unnatural and uncalled for. Mrs. Norris, knowing that her place is no longer welcome, since in the key test of the Rushfords and the Crawfords she had seemed to judge badly, has little choice but to acknowledge her failure and move out, leaving the field not to Fanny who has after all moved far beyond her and replaced Lady Bertram as the leading woman in the family, but to Sally, Fanny’s younger sister, who has now become the main companion to Lady Bertram. That defeat by two sisters must have been too much, though as usual Jane Austen does not describe the emotions that have overcome her at the prospect of Sally, but she does describe the statements Mrs. Norris makes about the inconsiderateness of the family to Maria, and those seem just. Mrs Norris goes off to live with Maria as two ladies alone, which is no great sacrifice to Mrs Norris, who gains a companion and who can live in a style appropriate to someone who has rage against an unjust world, just as Fanny would have lived with William, her brother, if the concatenation of circumstances had not worked out in her favor.

Mrs. Norris is thought badly for her candor in saying what Fanny had thought, which is that her acceptance of Henry Crawford would have averted the family scandal. The family is in no position to consider such possibilities, but in the tradition of Humean morality, feels such sentiments as its position now entitles it to, which is to think well of Fanny. This fact finally secures Fanny's position, since it is no longer a matter of mere sentiment, of charity un-buttressed by self-interest.

Sir Thomas has no good explanation to give for the series of family disasters. He turns to the usual set of banalities that are trotted out by parents and experts whenever children of any social class go bad. He says he was too permissive with daughters who had been flattered by Mrs. Norris, as if she had raised them, but who is now the repository of all blame. Fanny had turned out well because of her adversity. This is so lame as to be comic, since Fanny's mistreatment by Mrs. Norris had not bothered him so much before then that he had put a general stop to it, however benevolent he was in lightening her disapproval of Fanny by granting individual acts of mercy and graciousness. Who would have needed the mercy of this beneficent God if God had not established a cruel world to begin with? The reader is also aware that the benefit of Mrs. Norris’ attentions had driven Fanny even more deeply into herself, made her a more clever version of Mrs. Norris, who knew better than to speak out of turn, and accounted in part for her inability to respond to Mr. Crawford, because she did not feel she could possibly deserve such attentions, given her condition and defects, all of which had been made abundantly clear by Mrs. Norris.

So Lionel Trilling is correct to say that the ending of “Mansfield Park” does not leave us feeling good, even though it ends with the conventional marriage of erstwhile hero and heroine and their entering into the life they desired. The ending is not satisfying, however, not because our hero and heroine are such smug creatures, but because the novel never lets the reader forget that any number of other possible endings might have taken place, and that this particular ending is not so perfect, for it represents the fact that Fanny and Edmund are limited in their prospects, settled for what was comfortable rather than what might have challenged their souls. This is less upsetting in the case of Edmund, who was never very perceptive, once he got interested in women, and who seems to have the character of a clergyman, which he was gracious enough to accept without complaining, once he had no choice but to become one, just as Fanny has once silently accepted the fact that she would probably never consummate her love for Edmund. It is more unsettling when applied to Fanny, who after all had potential, had made herself into a creature of the gentry class, but could never force herself to brave it into London or polished society.

Fanny had done more than she could have been expected to do. She was a girl who was clever and deferential, who turned her reading and her brain into a way of moving up significantly in social class partly because she had no choice but to succeed or fail, to live up to the correct manners required of her since the day she arrived at Mansfield Park or else risk being shipped back if she should lose favor. She had to make the manners part of herself more than the others did because she was so dependant upon them, and so they took over her being in a particularly remorseless way, which made her constitutionally incapable of taking on the next leap and transforming her personality into one that could have managed the moral life of the London set, though there is no reason to think it any way worse than that of the men in the country set, who simply disappear for long periods to go hunting, drinking and wenching at a distance rather than close to home. It is, moreover, understandable that having partially gained acceptance at Mansfield Park, though by no means secured it, she would not want to take a risk with her new found selfhood to remake herself yet another time. She was too old for that. Jane Austen's protagonist is therefore only heroic to an extent, to the point absolutely required by her condition, and since her condition is so precarious, and has been so for so long, she cannot be expected to drain herself of her remaining psychological resources by daring again to remake herself. That would be foolhardy, even if the reader would like to believe his heroine could go on forever outwitting the world and conquering ever upwards. Trilling finds society oppressive because it isn't pure possibility, but has some resilience of its own, giving under concentrated pressure but not always yielding. Jane Austen, to the contrary, seems to think Fanny's achievement remarkable enough without requiring her to toss it all away to become someone who might not be able to cope with a husband’s philandering.

An even more deflating residue of the novel, however, is its depiction of the nature of moral life as that is successively redefined by the novel. Morality as generalized principle comes to replace a calculus of self interest. The last chapter of the novel suggests that generalized principle is not enough because the world gets turned so topsy turvy that it is not clear whether a generalized principle is a good enough guide to self interest. At the end, it seems that Fanny has been good because she has been Kantian. She has embraced principle for its own sake. She acts correctly regardless of consequence, and proves to impress the rest of the world with her moral rectitude. Morality is her power and her strength.

But this is a very flawed version of Kant. Fanny’s is still what Kant would call a prudential morality in that it is adopted for want of any better way to act. A person acts morally only because whatever calculus one makes may not work out. This level of ignorance makes it incumbent to act morally in the first place because if things go wrong then there is the satisfaction, at least, of having acted properly. This is appropriate in a topsy turvy world, but it is not what Kant meant when he said that moral action should be taken for the love of acting morally not for the sake of being known to oneself, much less to others, as a person who acts morally. Fanny may come to learn to be moral as well as to want to be moral, just as Pascal suggests that practice may lead to belief, but she is not there yet, and it is not at all clear that that would be such a good thing. In a prescient critique based on Methodism of what would become elaborated as Kantian ethics, Jane Austen notes the moral deficiency of this moral stance. It involves an inturning of the self, a loneliness which no communication can breech, for only in the self is it known whether an action was taken for the right reasons. Kant may want to turn humankind into a set of moral monads, each person operating as if they were totally independent in the world, and only fortuitously conjoining their actions, or doing so on the basis of high seriousness, rather than on the basis of the give and take of life, but Austen sees this as a sacrifice which Edmund, but more especially Fanny, makes. Fanny's strongest moral trait is her reticence, her unwillingness to speak what is unbecoming even to herself, and that means that her life is necessarily filled with unvoiced defeats and even tragedies and even successes. She cannot gloat, but neither can she savor; she cannot whine and browbeat, but neither can she express or seek the need for compassion. This removal from human life has made her triumphant, but more largely speaking, it is what she is.

In short, the critique of Kantian morality is that it removes people from people, supplies them with only, perhaps, their own heart to consult, and even that at considerable risk. Kantianism is thence not a triumph of reason but a retreat into the Romanticism that is on the rise in the world: a paean to emotion that comes from the fact that people have become self-enclosed and therefore preoccupied with self rather than because they have been liberated into new kinds of experience. Jane Austen, who lives on the cusp between Classicism and Romanticism, is not unmindful of the kind of liberation Romanticism supplies. After all, her own self is turned to the energies of art and the position of the observer, but she does not contemplate, here at least, the position of the heroic poet who acts, the Byronic figure, but considers instead, how much is given up by looking at the multifaceted self and not at the multifaceted social reality it reflects, for that is to take a self out of the action, out of an engagement with life, and means betraying the self. Fanny's final tragedy has nothing to do with whether she marries Edmund or not. It has to do with the creation of a self other than the Classical one, and the ambiguities that are resident in such a self.

What accounts for Fanny's rise in the world from a poor relation to the new daughter in the family who will soon be courted by a highly eligible bachelor, and whom Sir Thomas has come to treat as his own daughter, and whom he likes and respects more than his own daughters? The suspense of the novel is that Fanny seems sooner or later to be headed for a fall, either through circumstances, which would make it unfortunate, through the venality of others, which would make it melodramatic, or through her own character, which would make it tragic.

All of these possibilities are available. Fanny is both headstrong and remote, and so could miss an opportunity available to her, or blurt out the well merited grievances she has piled up against the family, and suffer the consequences of being ungrateful to those who think there is no end to the gratitude she should feel towards them. She might not be able to withstand the onslaughts of Mrs. Norris, who would do anything to turn something Fanny does against her, whether it were deserved or not; or Lady Bertram, who is so suggestible and weak that someone could turn her against Fanny, or might manage to do so herself if for some reason she took it in her head that Fanny had been insufficiently attentive; or the sisters, who have no great use for Fanny if she should become of sufficient importance to be noticed by them as something other than a dependant.

External events rather than family intrigue could also lead to Fanny's downfall. A turn in the family's fortunes, or a rearrangement of the family so that Lady Bertram would have to, let us say, take on Mrs. Norris as a permanent lady in waiting, or the need to pack off Fanny to serve that role for one of the sisters, would also lead to a reduction of Fanny from her recently elevated position to her "permanent" rank as a poor dependant. In any of those circumstances, Fanny might be turned against herself, reinterpreted herself as ungrateful, and so no longer secure in her insecure position.

None of these disasters come to pass even though the reader has been waiting patiently and deliciously for Jane Austen to invent a particularly clever and unexpected way for Fanny to fall, the novel serving as a kind of mystery story which provides clues but not the conclusion not to who done it but to how Fanny was done in. So the reader begins halfway through the novel to reread it for the reasons Fanny leads such a charmed life.

Fanny works her way into the good graces of the family because, first of all, they are not so grand as they make out. Sir Thomas had married considerably beneath him, for sentiment rather than good sense. He has a wife who needs constant attendance and is not much good for anything. But for her brief conquest, she might well have fared no better than her sister in Portsmouth who also married for love, but to less advantage. The work of Mr. Bertram’s' life seems to be to try to raise the sights of his wife and her relatives, to reach below him and provide civility to his inferior relatives, perhaps because that is the best such a soft hearted gentleman can be expected to do. In that case, Fanny appeals to him as another case to work on, and of considerably better capacity than the other materials he has tried to form, and so not so out of keeping with the rest of his life, either what he is doing now, or what he chose to do years before-- though it is to his credit that he does not harbor bitterness about past decisions.

Fanny is herself up to the task of being remade because she is more master of language than anyone else at Mansfield Park. She says things in the way they should be said or does not say them at all. She is not given to the gaffes of the rest, and so it is no wonder that Mary Crawford picks her out for friendship as one who can be talked to as a sister. Fanny is tongue-tied when she is called upon by Henry to say something to him, because nothing that she could say would tie together her feelings and her situation, but no one else in the family could have spoken with such candor to Mary, telling her that her brother was not to be trusted because he was a flirt, declaring her real motives in a morally appropriate manner, and so earn from Mary a laugh and a remark that acknowledge the truth of what she has said.

For this and other reasons, Mary takes Fanny to be the sort of person who could indeed rise up not only to the social class of the minor country gentry, but to the stature of the more worldly London families, who have their connections in the Admiralty and the other institutions that control English life, which is all the more reason why Mary is confused that Fanny would not take the opportunity to marry her brother, but seems instead to prefer the morality of country respectability, to which she and her brother have condescended with a liberality at once real and affected, as was the case with many Eighteenth Century city people who have nostalgia for what they see as an antiquated and disappearing but charming manner of life. Such a life is attractive to the Crawfords because it is a non-threatening alternative to their own insecure positions as the Fanny like relatives of a more distinguished family patron. They do not know that Fanny is shocked rather than sympathetic to their own view of the servility imposed upon distant relatives by the heads of families. They do not know that she is self-limiting and that therefore her failure to move up in society as far as she might could be considered tragic, our third possibility for explaining her fate, when it is, instead, settling for what she wants, and so not tragic at all, Jane Austen, among her other accomplishments in this novel, supplying an answer to the idea, which will become everywhere obvious in the Nineteenth and the Twentieth Century, that you are only satisfied if you go as high as you can. Jane Austen turns that wisdom on its head by declaring that people go only as far as they want to, and there are no end of sociological studies which justify the idea by showing that people do not go so much from the bottom to the top of the social ladder as move up one or two rungs in the course of their lives. Jane Austen explains why.