The transition in “Mansfield Park” from language that is occluded because it is calculated to language that is, by and large, in the clear because the characters have need of a language whereby they can express who they are, takes place at the same moment that is the pivotal point for the plot of the novel, which is when Sir Thomas Bertram returns from Antigua. Jane Austen seems to expect her more literate puzzle solvers to catch on to this union of her structural and language leverage points, and so see the Shakespearean allusion as well as the importance for the plot of weaving the change of language into the new developments in the plot, just as she expects her merely attentive reader to solve the puzzle of her characters if some attention is paid to the abundance of clues Jane has so thoughtfully provided to help the reader along.

The Shakespeare play that Jane Austen chose to rework as “Mansfield Park” is probably “Measure for Measure”. There, just as in “Mansfield Park”, a heroine who seems devoted to virtue comes to seem perverse because of her seeming unwillingness ever to consider prudence, even to serve, there, the interests of her brother, and in spite of the advice of all those who surround her. There is also an absent nobleman, who has allowed his society to run on its own dynamics, presuming these to be fixed, settled, and self-balancing, only to return to find that things have fallen apart, his society on the verge of some kind of moral anarchy. The general belief is that society can only be restored to its proper balance by the intervention of the returned leader, though it is not clear that he has either the understanding or the will to do so. The audience and the reader are left with the very sour feeling that people keep making messes of their lives, and will continue to do so, and manage to rectify things, if at all, only by redefining relative failure as relative success. Their problems arise not so much from tragic flaws, from their own or the universe's nature, but from thoughtlessness, stubbornness, and other minor vices.

As soon as Sir Thomas appears on the scene on his return from Antigua, there is an immediate change in the meaning of language. Now events which had been frivolous and words which had been meaningless take on their full resonance and meaning all at once, as if everyone had been removed to a higher level of understanding, the veil between illusion and reality suddenly lifted.

It is interesting to contemplate the first emotions people might have felt under this new dispensation. It might have been gladness, reasonability, sentiment, or any number of other emotions thought characteristic of the Eighteenth Century. Instead, the first emotion every character feels is guilt, even down to Fanny, who has least to feel guilty about since she had held out longest against the temptation of doing theatricals, even though she had at the end given in ever so little to it.

Sir Thomas forgives the family immediately, though Jane Austen suggests this has less to do with relenting from a deserved sternness that in his unwillingness to forego the pleasure of his reunion with his family. He does put an immediate end to the festivities, even if Yates, a friend of the family who had first proposed the theatricals, is so crude as to ask why everyone had done such an about face, and wonders what was so wrong with the theatricals, especially since Sir Thomas, perhaps out of a touch of guilt about having cancelled them, decides to give a ball that will serve as a kind of coming out party for Fanny.

The trouble with the theatricals is in part financial. Mrs. Norris is quick to note how much money she saved on the project, so everyone was at the time of their plans aware that they should not spend too much money. Sir Thomas was, after all, away in Antigua to straighten out their finances, and it is to be presumed, though Jane Austen does not say so in so many words, that the family was trying to live frugally until the economic problems were resolved.

There is a larger problem with the theatricals. They are a recipe for license because they allow people to proclaim emotions they do not feel which are of an intimate sort, or even worse, allow people to proclaim private feelings which they do feel, but which are not properly spoken of. The irony of this situation was lost on the characters, though not to the reader, before Sir Thomas' reappearance, but it is sensed as a careless form of liberation afterwards. It is not that the characters did not know before what they knew afterwards, but that they took it all more seriously, with more responsibility, as if now they had to be responsible for their actions when the presiding figure was present but were not responsible for their actions, did not have to act as other than children, when their father was away.

The reader is made ever more aware of the precarious hold morality has on Mansfield Park. Far from secure, morality is always challenged by the immoral ways of the country gentry young folk, the likes of Tom, Sir Thomas’ eldest son, who are always off on some misadventures which they can talk about only in the euphemisms of horseracing. Sir Thomas does not want his family's country respectability to give way to the looser morals of the large country estates or of the city.

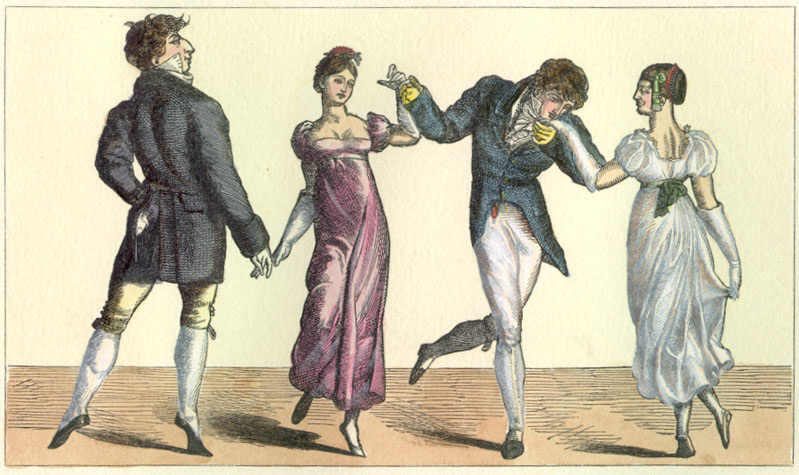

The ball for Fanny is not the same thing as theatricals, since it is a real rather than a fancied event, and so people will, if anything, act more properly than they otherwise might. It is also an event where there is sufficient formality and control by the elders so that flirting is kept within its proper bounds of providing indications of interest in pairing off. It is the kind of courtship which allows the passions to present themselves in a useful way, and it takes Sir Thomas' presiding genius to understand the delicate balance of pretense and compromise which allows the passions to be turned to useful arrangements, even if he is eventually to be overcome by his inability to manage things as well as he would have liked.

The play within a play that moves along the plot of the novel or play into which it is interpolated is, of course, an inheritance from “Hamlet”. Shakespeare is also known for his performances-within-performances, where characters go through set piece ceremonies where they each know what role they are supposed to play and, for some reason, fail to act properly. In the plays that precede the great tragedies, these performances are set towards or after the middle of the play and result in its subsequent events, and so function as the play within the play will function. Shylock is so overtaken by his rage that during the trial scene he drops the life long guise of magnanimity which he had adopted for the sake of prudence and so brings down all the evils which his Jewish soul had dreaded, by for once giving vent to his desire for vengeance. He for once holds a gentile to his promise, as he is presumably always held to his despite the entreaties of all the good gentiles that he act with nobility, even if the nobles engage in this performance of Christian virtue only this one time when the life of one of their own is at stake. Henry V, for his part, is remarkably passive, falling back on his old contemplative ways, when he listens to the explanation of his rights to the French throne, and unleashes the war as if he did not in that formal performance of his kingly role have the right to ask his advisors to reconsider, or give them new guidance about ways to deal with the French, who would probably have bartered their daughter for a peace treaty before as well as after the war.

Most of the time, however, the performances come close to the beginning of a play, as if the set pieces, the public occasions, generate the entire play or its most general movement when a key character misreads his role or perversely refuses to play it or somehow has risen beyond it. The intrigue in “Julius Caesar” emerges from the interpretation of what Caesar meant when he three times turned down the throne. Was it merely a performance, or an intention as well? There was nothing Caesar could have done within that performance that would have appeased his opponents. Hamlet suggests the depths of his own misanthropy and his preoccupation with his own cleverness when he plays on the pun of being a son during his formal reintroduction at the Danish court. Othello is better at declaring his love of state and of Desdemona at his formal return to Venice than he is able to avoid personal and social anarchy at the end of the play during the private performance of the confrontation scene he had set up in his mind. And, of course, both Lear and Cordelia both violate and uphold performance standards in the set piece that opens “King Lear”.

Jane Austen has a play within a play as a central moment of “Mansfield Park”, the point of which is that when people feign emotions they really have, as is the case when Maria plays opposite Henry, then people actually do perform the roles they have hesitated to perform in real life, and so reveal themselves more than is discrete, not because it is improper to be so forward, but because it is too emotionally destabilizing to act as if one is acting emotions which are not being merely performed but are in fact felt. People come to recognize themselves in their roles, or if they fail to do so, as is the case with the characters at Mansfield Park, it is not only a sign that they are obtuse, but are, in their own "real" world within the novel, merely prisoners of their roles, unsaved by circumspection and thoughtfulness, which is the virtue Jane Austen saves for herself and, occasionally, bestows on Fanny.

The characters do not know what to make of what they feel because they think they are merely playing roles, rather than displaying their feelings in public. Theatricals are a threat to social order not because they are play, but because they come too close to the truth. They serve the same purpose as a psychoanalytic session: they provide an occasion for the projection of feelings that are otherwise unnamed, and which are not less real because they are not attributed to the players during the dispensation of the performance.

The ball that Sir Thomas prefers to the theatricals is a performance within a performance that contains its own paradoxes and ironies. People at balls know they are feigning roles, while during the theatricals they do not know they are not merely feigning roles. At the ball, everyone cooperates to make Fanny look good, and so they discount what they are doing, though what they do not only succeeds in elevating Fanny's position in society, and her own self-esteem in a realm where, like Othello, she thought herself inadequate, but where her enthusiasms do not seem to create a disaster, her indulgence of her dreams of herself sustained rather than the object of humiliation, but where people do reveal themselves more than they want to, both Henry and Edmund coming off as her especial friends, which leads to the two courtships, one or the other either sacred or profane, that will dominate the rest of the book.

As Shakespeare knew, plays and performances are not fictions, but kinds of reality in which more is revealed than the characters recognize is revealed even if they see and are participants in the revelation. While Shakespeare may consequently have seen theatrics and performances as metaphors for religious conversion, Jane Austen simply regards them as methods and mechanisms for the continuing unraveling of character which is the nature of life in the world, and the ultimate justification of fiction.